Part 3

Skillful Risk Control Amid Endless Uncertainty

“The worst investments are made at the best of times.” – Unknown

Warren Buffett also said: “Risk comes from not knowing what you are doing.” In the game of buying unpopular stocks, if you don’t analyze long-term economics of the business, you are engaging in risky business. You won’t know whether you paid too much for it until it is too late. Understanding what you are investing in is one of the only ways to mitigate some risk.

As Buffett says, “I never buy anything unless I can fill out on a piece of paper my reasons why. I may be wrong, but I would know the answer to, ‘I’m paying $32 billion today for the Coca-Cola Company because…’ If you can’t answer that question, you shouldn’t buy it. If you can answer that question, and do it a few times, you’ll make a lot of money.”

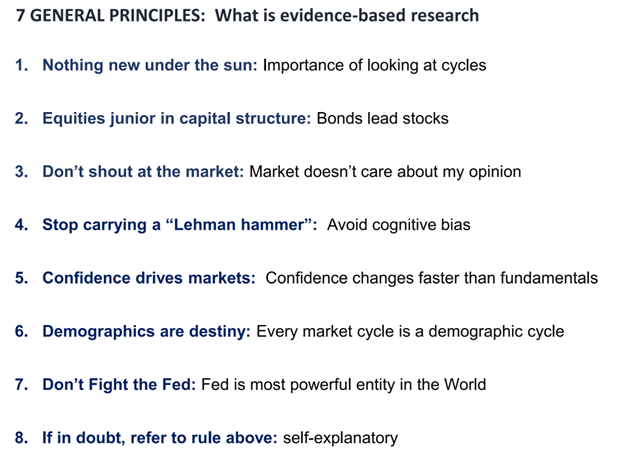

The most important part of a plan, then, is planning on your plan not going according to plan. Nothing is entirely predictable. The German physicist Werner Heisenberg, who came up with the Uncertainty Principle, discovered that even if every single initial condition is known, it is still impossible to predict with any fixed certainty the behavior of waves and particles. Likewise, chaos theory explains how even things on a bigger scale, like weather and the stock market, are not entirely predictable. They can’t ever be. Similarly, neuroscientists have shown us that the structure of our brain, and the nerve cells within it, also act with elements of randomness. A key defining feature of the universe is uncertainty. There is always a space for change, for the unknown. The universe and markets are an ever-evolving possibility.

In investing, it’s easy to be grateful for the power of markets when things are going well. But when the tide breaks against an investor—it happens to even the most seasoned veterans—how do we grow from the experience? Challenging markets can strengthen us.

We learn things about ourselves our portfolio, our risk profile, and goals in down markets that we never could have learned in bull markets. What lessons do we learn? How do we not complain about things outside of our control, but rather see the positive in what ended up happening, and use that information to make better decisions moving forward? Behavior in challenging markets is what sets investors apart. Some of the greatest returns in history have originated in anxiety-filled markets, when the risk seemed higher than it truly was.

In all aspects of our life, we make our decisions based on what we think probably will happen. We expect results to be close to the norm. But it could be better or worse. And we should bear in mind that there are outliers. Take the S&P 500: Most investors in index funds that track the major average can average an 8% return a year or so over decades. But the return in any given year is rarely 8%: It’s usually more or less. Sometimes, it’s much more or less. Because let’s face it: In the short run, investor psychology, not fundamentals, moves markets.

This sound familiar?

- The stock market moves into a bull cycle

- Investors reap the benefits, increasing their positions and risk

- Because bad news is scarce, the risks entailed seem to have shrunk

- Risk averseness virtually disappears

- Investors continue buying as markets rise

- Eventually, the bull cycle ends, and markets move lower; usually via the elevator (“The air goes out of the balloon much faster than it went in.”)

Then this process is reversed:

- Losses cause investors to become discouraged and shy away

- Risk averseness rises, cutting their positions and overall risk

- Less is made in gains, and at the trough of the cycle, few are optimistic enough to make risky investments at a time of relatively low risk

- Investors hesitate to buy at the (usually) best time to buy (trough)

- Eventually, the bear cycle ends, and markets move higher

Here’s Rick Funston of Deloitte & Touche, When Corporate Risk Becomes Personal: “You need comfort that the risks and exposures are understood, appropriately managed, and made more transparent for everyone. This is not risk aversion; it is risk intelligence.”

Investors overvalue companies when things are going well and undervalue them when things are going poorly in the economy. Well-run economy, surging markets? We lose a sense of risk. Chaos, pessimism? We lose willingness to bear risk.

In the end, we hope this three-part guide helps you understand a little more about risk in markets. The idea is that you must take risk to get ahead. The best investors over long periods of time know their own risk tolerance by heart, with a clear objective, and an acute awareness of their time horizon. They maintain a relatively diversified portfolio of positions they know well. They allocate to various asset classes. And they usually keep buying, sometimes via dollar-cost averaging strategies, to remove most of the risk of timing the market wrongly. This also enables them to buy at low prices, during max pessimism, when risk is usually lessened.

“Risk-taking is an inevitable ingredient in investing, and in life,” financial historian and economist Peter Bernstein once said, “but never take a risk you do not have to take.”